May 26th 2005 | WASHINGTON, DC

From The Economist print edition

Why is America returning to the moon, and what does the new “vision” for NASA mean for science?

THE name Eugene Cernan means little to most people, though space nerds may remember it. Along with more famous astronauts such as Neil Armstrong, Mr Cernan played a role in the annals of space exploration by walking on the moon. And he was the last to do so, which is fame of a sort. If George Bush gets his way, however, this claim to fame may vanish. That is because Mr Bush has a vision. He wants humans to return to the moon by 2020. The questions are, first, what for? And, second, having been given such orders, what will Mike Griffin, the new boss of America's space agency, NASA, do to execute them?

The second question seems more urgent because Mr Bush's initial goal is to reinvigorate an agency that is facing both the withdrawal of its flagships, the still-grounded space shuttles, and the failure of the international space station to deliver anything remotely approaching an interesting scientific result.

Some of the details about how Dr Griffin proposes to execute Mr Bush's vision emerged at the International Space Development Conference held in Washington, DC, last week. For example, NASA announced a $250,000 prize for extracting oxygen from the lunar regolith.

Where the Earth has soil, other rocky bodies in the solar system have regolith. Soil is, in part, the product of biological activity (all those earthworms, and so on). Regolith is a fine powder formed by a constant rain of small meteorites that breaks up the rocks at the surface. Analysis of lunar regolith brought back by Apollo missions shows it contains lots of oxygen. Existing ways of extracting this oxygen, however, are too slow to be useful. So a competition called the MoonROx challenge is being mounted. The prize will go to the first person to come up with a way of quickly extracting an adequate amount of oxygen from simulated lunar regolith (volcanic ash is being used as a stand-in).

Oxygen, though, is only the beginning, according to Paul Spudis, a planetary scientist at Johns Hopkins University who was a member of the president's vision commission (yes, there really was one). As he puts it, a cubic metre of regolith contains, besides the necessary oxygen, enough hydrogen, carbon, nitrogen, potassium and other trace elements to make two cheese sandwiches on rye, two colas and two large plums. Despite mythology to the contrary, though, the moon isn't actually made of cheese. So extracting this bounty is another matter. Whether the moon's natural resources can be used profitably remains, says Dr Spudis with nice understatement, a “key question”.

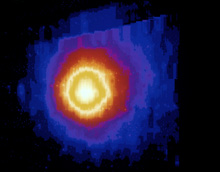

Those resources consist of a lot of rock, a lot of sunlight that could be used to generate electricity to process the rock and, at least in the dreams of many lunar scientists, some 20 billion tonnes of frozen water believed to lie at the bottoms of craters near the poles, where it is sheltered from the evaporative effects of sunlight. In addition to these goodies, the solar wind carries light elements such as helium to the moon's surface and leaves them there. Some visionaries think that this helium might find a market on Earth, though its main use would be in fusion reactors that do not yet exist. And there are also likely to be deposits of platinum and other valuable metals contained in asteroids that have crashed into the moon.

The least certain item on this list is the water. Evidence, but not proof, of its existence was found by two earlier missions. So the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter that NASA plans to launch in 2008 will search more thoroughly, and will also make detailed maps that should help to find good spots to land. Dr Spudis, though, already has a favourite. A crater at the south pole called Shackleton has a rim that is bathed in sunlight for more than three-quarters of the time (as opposed to half the time for most of the moon's surface). That makes it easier to generate electricity. The bottom of the crater, by contrast, is perpetually dark and, with luck, ice-bound.

It all sounds jolly ambitious. But establishing a human presence on the moon itself is not, actually, Mr Bush's ultimate ambition. He wants humans to explore the cosmos—or, at least, Mars. The moon is merely a stepping-stone; a place to teach people about living on other worlds. New survival technologies and systems developed on the moon will then be employed on Mars. These include better collaboration between people and robots, durable technologies for survival in hostile environments, better “closed-loop” recycling systems for the re-use of resources, and improved telemedicine. Practising on the moon makes sense because it is only three days travel from Earth.

According to Rick Tumlinson, president of the Space Frontier Foundation, a space advocacy group, this difference of emphasis between going to the moon for its own sake, and using it as a stepping-stone, illustrates a wider problem for NASA, which is that people disagree about what the vision really means. Since it was announced, says Mr Tumlinson, the vision has been an “all-spin zone”, with everyone spinning his own version. To some, it means mining the moon for helium or platinum. To others it is about building a lunar observatory. A third group wants to collect solar power and beam it to Earth. To the most ambitious, such as Mr Bush himself, it means that humanity is going to explore the rest of the solar system in person. And Mr Tumlinson's particular spin? “It's about permanence. We go to stay. It's about settlement and changing our culture. What you don't do is Apollo on steroids.”

Dr Griffin, therefore, has the difficult job of charting a course among these competing mini-visions. For, while Mr Bush and his vision are obviously going to be in the driving seat for now, that will not always be true. As Admiral Craig Steidle, the associate administrator of NASA's office of exploration systems, observes, the most difficult aspect of the vision is “sustainability”. By this he means keeping it intact through successive Congresses, administrations and NASA chiefs, who may have different visions, and also in the face of an increasingly vocal lobby that feels the private sector is being overlooked, visionwise.

Perhaps, though, whether the vision can be realised or not is beside the point. The actual point is to give a drifting agency some focus, Mr Bush's initial goal. This re-focusing will have profound consequences for the agency's scientific mission—which some people feel is what it should be concentrating on, and isn't. Admiral Steidle told the meeting that the vision was “first and foremost” about advancing science. That, though, looks like disingenuous spin.

NASA will undoubtedly need science to achieve the vision, whatever it turns out to be. And there is undoubtedly lots of interesting science to be done on the moon. But if scientists were running the show, and acquisition of knowledge were NASA's top priority, they would be unlikely to spend $64 billion over the next 15 years on a manned trip to the moon.

Instead, scientists would prefer to build space telescopes to probe the origins of the universe and search for Earth-like planets around other stars, launch an unmanned mission to Jupiter's fascinating moon Europa, and fund the Glory mission, which is designed to answer crucial questions about the Earth's climate. And they would still have a lot of money left over.

But lunar science, and lots of it, is what they are going to get. For the real point of the vision, whatever form it takes in detail, is to put human exploration first and scientific discovery second. And that truly is back to the future for NASA, for the Apollo project had exactly the same priorities. Harrison Schmitt, Eugene Cernan's even more forgotten companion on the last Apollo mission, was the first and only scientist to make the trip. Even in the agency's heyday, NASA's scientists came second.

Copyright © 2005 The Economist Newspaper and The Economist Group. All rights reserved.

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

WELL WHAT DO YOU THINK, WILL WE MAKE IT BACK TO THE MOON? - LRK -

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.